Conductive hearing loss

Authors: Diane Lazard, Benjamin Chaix

Contributors: Sam Irving

The decrease in auditory acuity seen in conductive hearing loss is caused by pathology of either the outer or middle ear. The most common pathologies are covered in this chapter, but this list is in no means exhaustive.

Disorders of the outer ear

Symptoms: pain (oralgia), pussy or hemorrhagic discharge (otorrhoea), decreases in hearing.

Clinical and etiological examination:

Pinna disorders: change in shape, otalgia.

- Cutaneous causes: eczema, psoriasis, boils, mycoses.

- Traumatic causes: subcutaneous haematoma (othematoma). Without treatment, the ear can harden in its disformed state, giving rise to ‘cauliflower ears’

- Infection of the cartilage (chondritis): hot skin with lesions (pus, welts…). The main risk here is the deterioration of the pinna. Particular attention should be paid to piercings in the cartilage as these are a main contributor to chondritis (see picture).

In these cases, hearing loss is caused by a mechanical occlusion of the external auditory meatus.

Disorders of the ear canal:

- Build-up of wax: this is the most common cause of conductive hearing loss. It can also lead to otalgia and infection (external otitis).

- External otitis: This is infection in the skin of the ear canal. Its symptoms are intense otalgia and pussy discharge (see picture).

In these cases, hearing loss is caused by a mechanical occlusion of the ear canal.

A conductive hearing loss caused only by a problem with the outer ear cannot cannot cause a loss of more than 30 dB.

Disorders of the middle ear

Hearing loss caused in the middle ear are classified into two categories: conductive hearing losses with an abnormal tympanic membrane, and those where the tympanic membrane is normal. They both share the same acoumetric and audiometric characteristics (see the chapter on functional assessments):

- Lateralised Weber test towards the side with hearing loss. Rinne: Air conduction < bone conduction.

- Decrease in air conduction but normal bone conduction

- Lack of stapedial reflex.

- Speech audiometry shifted towards the right, but reaches 100% at higher intensities. Maintains the normal sinusoidal shape.

Conductive hearing loss with a normal tympanic membrane:

What is a ‘normal’ tympanic membrane?

A normal tympanic membrane is thin and transparent, allowing visualisation of the air in the tympanic cavity. The malleus (hammer) is the only ossicle that contacts the membrane directly.

This image shows a healthy tympanic membrane, with the malleus (1); the pyramid of light reflecting the light from the otoscope (2); the opening to the eustachian tube seen through the membrane (3); and the pars tensa and promontory (4), also seen through the tympanic membrane.

Otospongiosis

Symptoms: hypocusis, presence or not of tinnitus, dizziness.

Otosclerosis: decreased motility at the join between the stapes and the oval window. Acquired hearing loss (generally appears in adults), but has an dominant autosomal genetic component with a variable penetration. It evolves to become layrinthitis and can be treated by surgery or auditory prostheses.

Cranial trauma

Cranial trauma can lead to separation or fracture of the ossicular chain with no sensorineural effects.

Symptoms: hypocusis, otalgia, (rarely) facial paralysis.

Conductive hearing loss. Increased compliance. Depending on the dislocation site, the ipsilateral and contralateral stapedial reflex can be affected.

Diagnosis requires a scan, and treatment comes in the form of surgical intervention (ossiculoplasty).

Abnormalities in the ossicular chain: minor aplasia.

Aplasia in the ossicular chain has a prevalence of around 10 in every 20000 births and is bilateral in around 30-40% of cases. Malformation of the ossicles can also be accompanied by abnormal pinna and/or ear canal development. The inner ear is generally normal.

Symptoms: conductive hearing loss

Diagnosis is by scan, and treatment can be either surgical or prosthetic.

Conductive hearing loss with an abnormal tympanic membrane :

Acute otitis media: acute infection of the middle ear cavity, which fills with fluid.

Symptoms: otalgia, fever, hearing loss.

Causes are generally bacterial, but can also be viral.

Very common in children under the age of 2 years, but can be seen at any age.

Requires rapid care as it can lead to complications and infection of the posterior cavities (known as mastoiditis). There is also a risk of meningitis and brain abscess.

Myringotomy is commonly undertaken to reduce pain and fever, as well as allowing a bacteriological sample to be taken for testing.

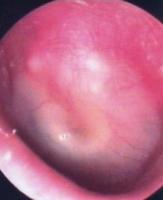

Inspection of the eardrum on the left shows an acute otitis media: the eardrum has thickened, become opaque and bloated, with visible hypervascularisation. The malleus is less visible and its handle causes a depression at its join with the tympanic membrane. Pus is also visible behind the membrane (yellow), and the pyramid of light is absent.

Otitis media serosa: this is cause by excessive serous fluid in the middle ear caused by decreased airation by restriction of the eustachian tube.

Symptoms: hearing loss, slight otalgia, a feeling of being blocked up.

Very common between 2 and 4 years, but can also occur in adults. One possible treatment is the use of a tympanostomy tube (“grommets”; see photo).

In adults, it is important to rule out a potential tumour of the the tympanic cavity.

Aftereffects of otitius media serosa: This image depicts an atrophic tympanic membrane, leading to a general retraction of the membrane and causing a reduction of the volume of middle ear (also known as middle ear atelectasis).

Note the retraction of the eardrum in the pars flaccida (1), the malleus is abnormally visible as it has been molded by the retracted membrane (2); the incus also has abnormal contact with the membrane (3). Retraction of the tympanic membrane is also visible in the pars tensa (4).

Tympanic perforation:

Symptoms: hearing loss (<30 dB if isolated), and some associated otorrheoa.

Otoscopic characteristics: central perforation (with respect to the the annular ligament).

Can be treated surgically by closing the perforation (tympanoplasty).

If the hearig loss is greater than 30 dB, damage to the ossicular chain should be investigated.

Pockets of tympanic retraction and cholesteatoma:

Symptoms: hearing loss with or without otorrhoea.

This is caused by repeated otitis during childhood and is an evolutive disease of the middle ear that damages adjacent structures. Development is slow but can be serious (meningitis, facial paralysis). The first stage is the pocket of retraction, which can then develop into a cholesteatoma (a tumour in the epidermis which is benign but grows slowly but aggressively, damaging middle ear structures and even the inner in in extreme cases).

Otoscopic characteristics: peripheral perforation, enlargement of the bone. In fact this case isn’t a real perforation as the eardrum is still intact, it has just been sucked in towards the bottom of the tympanic cavity.

Cholesteatoma is characterised by an accumulation of squamal cells in the retracted region. A break in the ossicular chain is classic, and it can sometimes affect the inner ear, which is reflected in a mixed hearing loss (reduction in air and bone conduction). In most cases, treatment involves surgery.

Fibroadhesive otitis:

Symptoms: hearing loss.

This is an inflammation of the tympanic cavity and the eardrum. Symphysis of the eardrum and the mucous in the middle ear by inflammatory connective tissue.

Otoscopic characteristics: thick, opaque tympanic membrane. No structures are identifiable.

Develops to a mixed hearing loss.

Unfortunately, little can be done to treat this condition.